Dementia, Confabulation, Conflation, And “The Truth”

Updated May 13, 2020

Think of dementia, confabulation, conflation, and the truth as ingredients in a recipe. In fact, let’s just say we’re making pasta sauce; we’ll put aside dementia, confabulation, conflation, and the truth over to the side for a moment.

The Ingredients

My pasta sauce recipe is roughly this:

- Some tomato sauce…or tomato puree

- Some tomato paste

- A little water

- Some roasted red peppers…or yellow…or orange…or green

- Some zucchini

- Maybe some broccoli

- Definitely spinach

- Mushrooms, maybe

- A whole mess of roasted garlic

- A lot of Italian seasoning…or fresh rosemary and basil and oregano

- Some pepper

All that goes in a crock pot, and when the meatballs (any combination of ground beef, ground sausage, ground lamb) are ready, I toss those in too. And a little pepperoni, if there’s any on hand.

The Results

I like the results, and so does my family. If you followed my recipe, would your result taste the same as mine? Maybe, but probably not; mine never turns out the same way twice.

Does my recipe resemble yours, or is it not even close? Are you thinking, Who has time to make it? I buy it at the store like the busy person I am!

Whatever your version, you call it pasta sauce, just like I call mine pasta sauce. And though you’ve never tasted mine, or maybe thought the recipe was weird, you knew what I was talking about, right?

Now, let’s get back to dementia, confabulation, conflation, and the truth. Because, believe it or not, it’s a lot like pasta sauce.

Different Versions of The Same Thing

Your version of the truth may be different than mine. That doesn’t mean I’m a believer of alternative facts, but if you think it does, you just conflated the two. See how that works?

A perfect example of your version of the truth vs my version of the truth is that old story about the two sons. One son is very successful, highly respected in his profession, happily married, a doting dad, and a guy who just loves his life.

The other son doesn’t really trust people. He tends to think everyone is out for themselves. He’s burned through numerous jobs, homes, relationships. He burns bridges with alacrity.

The sons sound quite different, but they both give the same reason for why their lives turned out as they did: their dad. Their dad was an abusive alcoholic who couldn’t hold a job, who never expressed affection, who was horrible to their mom. And both sons say, “With a dad like that, with that guy as an example, how could I have turned out any different?”

Which son is correct?

They both are: they’ve each lived their own truth. No alternative facts necessary, just their own interpretation of how the truth affected them. And, of course, how our brains record information.

Not Necessarily…As They Were

“Remembrance of things past is not necessarily the remembrance of things as they were.” ― Marcel Proust

In the United States, we observe Memorial Day on the last Monday in May, recognizing American service members who’ve died. It wasn’t always this way: its origins have been disputed regionally, the day has changed, and the original purpose was to honor Confederate soldiers who died during the Civil War.

It’s interesting to read the official version, and it’s also beside the point. The main idea is about honoring those who’ve made the ultimate sacrifice. Sometimes we get so caught up in details, in trivia, that we completely miss the larger point.

When it comes to communicating with people living with dementia, we as care partners sometimes get mixed up about what the point is. We get mired in meaningless minutia and we miss the point altogether.

We don’t recognize that dementia, confabulation, conflation, and the truth are often mixed together like ingredients in a recipe. Unlike in the kitchen, we don’t have any control over the ingredients. What we do have control over, though, is how we react. And that’s all we have control over, because we can’t change the ingredients.

I’ve too often witnessed a person living with dementia–clearly glorying in telling a cherished story–get shut down by a family member: “No, that’s not how it happened. I was born first! You’re telling about when Gina was born!” or, “No, we didn’t meet at the Lamplighter Lounge! We met at Amy’s party. You must be thinking of that tart you were seeing before me.”

Getting Bogged Down

Dementia aside, we seem okay with accepting the notion that we all have our own truth. We know that multiple eyewitness accounts of an event will result in multiple differing accounts of that event.

We evolved beings can live with that, but when it comes to our parents or partners erroneously reporting details that don’t have any bearing on the overall point, we won’t stand for it.

When we nitpick someone living with dementia because he’s not accurately recalling the details of a story by heart, we’re getting bogged down with trivial concerns.

Does it feel trivial to you? Of course not! It’s often painful, especially when it’s a cherished story. Who wants to be confused with someone else?

But that’s the thing: we’re talking about someone we love, someone whose brain is under attack by a disease process that causes confusion.

So why do we struggle to let people we love–people whose brains are under attack–make an error and graciously accept it?

Why are we more compassionate with a stranger telling his own truth?

What’s Really Happening

Becoming familiar with the relationship between dementia, confabulation, conflation, and the truth allows care partners to understand what’s really happening when a loved one is telling a story and mixing up the details.

“In psychiatry, Confabulation (verb: confabulate) is a memory disturbance, defined as the production of fabricated, distorted or misinterpreted memories about oneself or the world, without the conscious intention to deceive.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Confabulation) (Emphasis is mine.)

That part–”without the conscious intention to deceive”–is really important to hold on to. It’s another piece that allows us to understand none of this is on purpose. Confabulation is no more an intentional action than developing dementia.

Conflation isn’t intentional, either. It happens when two or more distinct pieces of information are combined to create a new “fact.” Voila, confabulation.

In cooking terms, it looks kinda like this:

Mix 1 can of tomato paste [Random Fact #1] with

1 gallon of crushed garlic [Random Fact #2]

= Delicious pasta sauce! [New fact (that’s usually as unappealing as this example)!]

In reality, it could look like this:

I can’t find my purse. [Random Fact #1]

+ My daughter visited last night. [Random Fact #2]

= My daughter is a thief who can’t be trusted! [New fact!]

Great, right? Now you know why it’s happening, so all you have to do is explain to your parent or partner why they’re wrong, yeah?

Nooooooo! You’d be using reason and logic to do that, the fuel that powers executive function. And by the time we’re trying to figure out dementia, confabulation, conflation, and the truth, executive function has pretty much gone AWOL.

But if you want to get into an argument, that’s a quick way to get there.

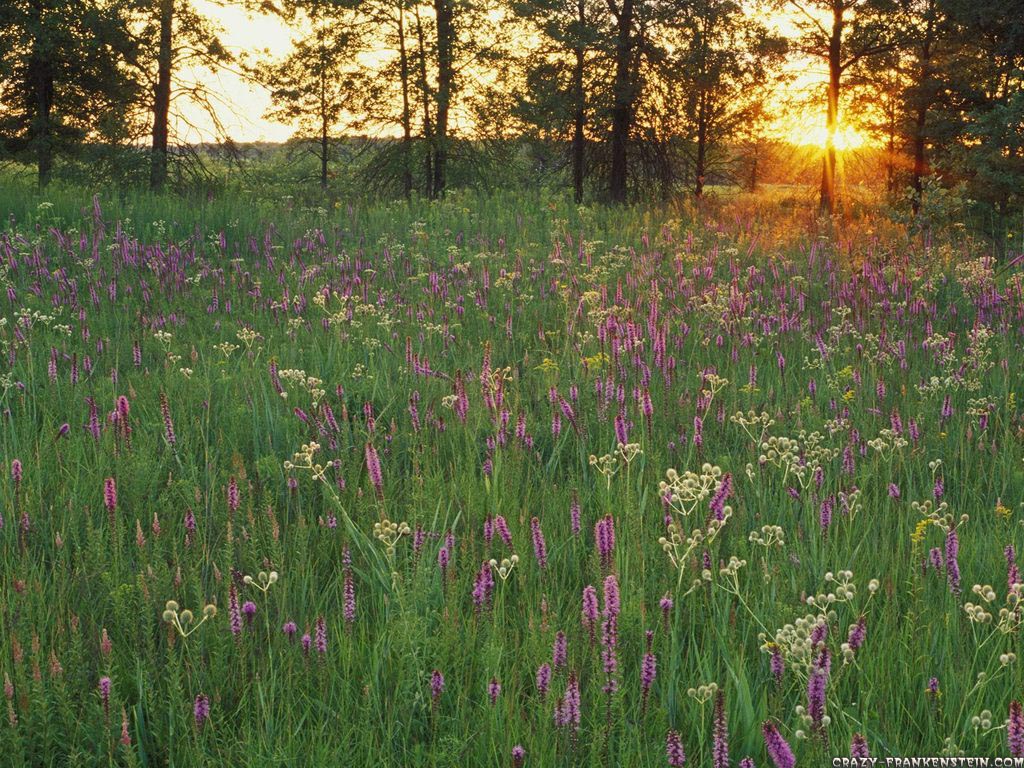

Be A Charming Gardner!

Understanding that dementia, confabulation, conflation, and the truth get mixed up like ingredients in a recipe–one that’s beyond our control!–allows us to offer grace notes to the people we love.

Rather than getting caught up in the details, try thinking about it differently. When your person is telling a story, celebrate! Engage them. Listen closely. If you have the presence of mind, whip out your phone and record it.

Of course, there’s always the possibility you’re the one recalling the story incorrectly, but if not, celebrate the wins in this moment: this person you love is engaging with you! She’s able to speak, to produce a coherent narrative.

Your loved one is trying to connect with you, telling a story that has meaning and resonance for him. To truly understand the story, look for what’s under the dementia, confabulation, conflation, and “the truth.” Listen for the emotion behind the words and the details. That’s where the real story lies. That’s the detail that actually matters.

“Let us be grateful to the people who make us happy; they are the charming gardeners who make our souls blossom.”― Marcel Proust